More details

Executive Summary

Also available in Bosnian.

SDG Performance and Challenges in Europe

Ending the COVID-19 pandemic everywhere is a prerequisite for restoring and accelerating SDG progress in Europe and globally. The pandemic halted progress towards achieving the SDG goals in Europe and elsewhere in 2020, reducing life expectancy and increasing poverty and unemployment rates in many countries. As of early November 2021, 65% of people in high-income countries (close to 70% in the EU27) were vaccinated, against 2% in low-income countries for which data is available. The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the grave inadequacy of global public health emergency preparedness and inequity in responses. Increased financial resources for health in the Multiannual Financial Framework and EU4Health work programme 2021-2027 and the strengthened mandate of the European CDC and the European Medicines Agency should augment health preparedness and coordination in the EU in line with SDG 3 (Good health and well-being). As emphasized under SDG 17 (Partnerships for the goals), Europe must continue to work with the United Nations, the G20, the G7 and other key partners to accelerate the roll-out of vaccines everywhere and to address the lack of fiscal space to finance emergency expenditures and recovery plans in low and middle-income countries.

The pandemic is a setback for sustainable development in Europe, but the SDGs should remain the guideposts. For the first time since the adoption of the SDGs in 2015, the average SDG Index score of the EU did not increase in 2020 - in fact it slightly declined in the EU27 on average mainly because of the pandemic's negative impact on life expectancy, poverty and unemployment. Despite geopolitical tensions and calls to scale back SDG ambitions, the SDGs remain the only integrated framework for economic, social and environmental development adopted by all UN Member States. The EU should continue to play a leadership role in implementing the goals internally and internationally in the run-up to the SDG Summit in September 2023 and beyond. Coordinated efforts to effectively implement EU recovery plans and the ambitious policy and financial instruments adopted in 2020 and 2021, including the Recovery and Resilience Facility, can provide strong support for the UN Decade of Action for the SDGs.

The SDG Index across the EU27 countries has declined slightly in 2020 for the first time since 2005 due to COVID-19

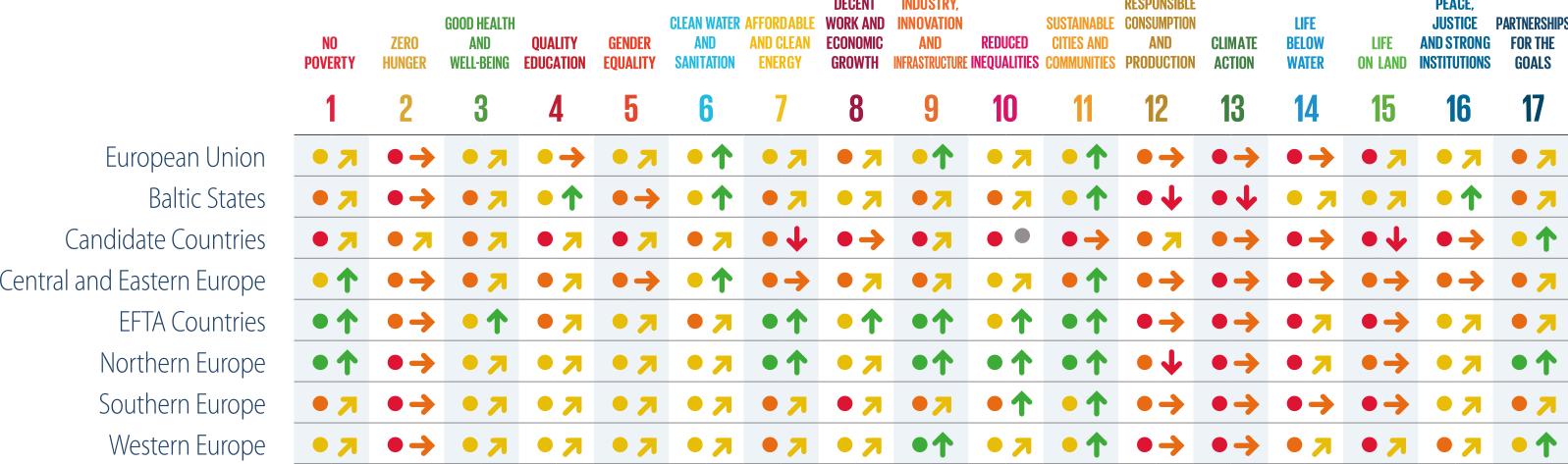

Note: Population-weighted averages for each sub-region. Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Candidate Countries: Albania, the Republic of North Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Turkey. Central and Eastern European Europe: Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovak Republic and Slovenia. Northern Europe: Denmark, Finland and Sweden. Southern Europe: Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal and Spain. Western Europe: Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. EFTA Countries: Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. Source: Authors

SDG Index Score, EU27, 2015-2020

Source: Authors

Europe faces its greatest SDG challenges in the areas of sustainable diets and agriculture, climate and biodiversity (SDG2, 12-15), in strengthening the convergence of living standards across its countries and regions and needs to accelerate progress on many goals. Finland tops the 2021 SDG Index for European countries (and worldwide), as it was less affected by the COVID-19 pandemic than most other EU countries. It is followed by two countries also from Northern Europe - Sweden and Denmark. Yet, like the rest of Europe, these countries face significant challenges in achieving SDG targets in the areas of sustainable diets and agriculture, climate and biodiversity, partly due to international spillovers - such as deforestation - embodied into trade. The pace of progress on many goals is generally too slow to achieve the SDGs by 2030 and the Paris Climate Agreement by 2050. Candidate countries perform well below the EU average, although they were making progress before the pandemic hit.

2021 SDG Dashboards for Europe

Countries that achieve better results on the SDG Index also achieve better results in the 'leave no one behind' Index

Note: The 'leave no one behind' (LNOB) Index measures inequalities across population groups in each country. It focuses on four dimensions: (1) Extreme Poverty and Material Deprivation; (2) Income inequality; (3) Gender inequality; (4) Access to and Quality of Services for all. It is based on 31 indicators. The graph shows the rank correlation between the LNOB Index and SDG Index (r=0.88). See methodology section for more details. Source: Authors

The recovery and pursuit of climate and biodiversity targets must be accompanied by ambitious social policies to “Leave No One Behind” and solidarity. Vulnerable groups and populations - including poor people, women and migrants - have been particularly affected by the health and socio-economic impacts of the pandemic, in Europe and in the rest of the world. Yet strong automatic stabilizers and deliberate policies to protect the economy and people helped mitigate the SDG impacts of COVID-19 in Europe compared with most other world regions. Countries that top the SDG Index also top the 'leave no one behind' (LNOB) index, indicating that sustainable development and the reduction of inequalities are mutually reinforcing goals. At the international level, COP26 in Glasgow emphasized the need for ambitious climate pledges and actions to be accompanied by strong social policies and international solidarity to support vulnerable countries and populations.

Further efforts are needed to strengthen the convergence of living standards across European countries. SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) calls for reducing inequalities across countries, generally referred to as 'convergence' in Europe. Our findings suggest that SDG 9 (Industry, innovation and infrastructure) is the goal with the broadest spread in performance across European countries, with many performing very well (scoring 'green' on the dashboard) but also many performing very poorly ('red' on the dashboard). Education and innovation capacities must be strengthened to accelerate the convergence in living standards across EU member states as well as in candidate countries. The SDGs provide a useful framework for constructive dialogue and exchanges between the EU and candidate countries in the Western Balkans.

Europe is the SDG leader globally, but generates negative international spillovers. In our 2021 global SDG Index, the ten top-ranked countries are European (nine are EU member states). In fact, all countries in the top 20 apart from Japan are European. Many European countries also appear at the top of the rankings as the happiest countries in the world in the 2021 World Happiness Report, also published by the SDSN. With the adoption of the European Green Deal in 2019 and related legislation including the climate law and the fit-for-55 package, Europe was the first continent to announce a bold commitment to climate-neutrality by mid-century. In doing so, Europe acts as a global standard-setter. Yet, major SDG challenges remain in all European countries and further effort is needed to align Europe's domestic transformations with its external relationships and cooperative endeavours. Our International Spillover Index suggests that European countries generate sizeable negative spillovers outside the region - with serious environmental and socio-economic consequences for the rest of the world. For instance, imports of clothing, textiles and leather products into the EU are related to 375 fatal workplace accidents and 21,000 non-fatal accidents every year. Other prominent examples of how current consumption in EU countries contributes to environmental degradation outside Europe include deforestation and biodiversity loss driven by trade in timber, palm oil, coffee, rubber, soy and other commodities.

The EU27 is the SDG leader globally but outsources economic, social and environmental impacts abroad notably through trade

Note: The Spillover Index measures transboundary impacts generated by one country that affect the ability of other countries to achieve the SDGs. The Spillover Index incorporates environmental and social impacts embodied in trade and consumption (negative spillovers include CO₂ emissions, biodiversity threats, and accidents at work), financial spillovers (such as financial secrecy and profit shifting), and security/development cooperation spillovers (ODA and weapons exports). ODA is an example of a positive spillover. Scores should be interpreted in the same way as the SDG Index, ranging from 0 (worst performance/significant negative spillovers) to 100 (best possible performance/no significant negative spillovers). To allow for international comparisons, most spillover indicators are expressed on a per capita basis. The Spillover Index scores and ranks are available online at www.sdgindex.org. Source: Sachs et al, 2021

There is no sign of decoupling between economic growth and environmental spillovers embodied into EU consumption. Through imports, for instance of cement, steel and fossil fuels - Europe generates CO₂ emissions in other parts of the world, including Africa, Asia-Pacific and Latin America. While domestic CO₂ emissions have decreased on average in the EU since 2015 - despite significant differences across EU member states and claims that the pace of decoupling remains insufficient to achieve net-zero by 2050 (Bruegel, 2021) - CO₂ emissions emitted abroad to satisfy EU consumption (so-called imported CO₂ emissions) increased by around 3.5% in 2018, a faster rate than GDP. EU food supply chains also generate substantial negative impacts, in terms of biodiversity threats to biodiversity and land use in the rest of the world. Decoupling socio-economic progress from negative domestic and imported impacts on climate and biodiversity requires further effort, through domestic actions and international cooperation.

CO₂ emissions generated abroad to satisfy EU's consumption of goods and services grow faster than GDP

Note: Imported CO₂ emissions refer to CO₂ emissions emitted abroad (e.g. to produce cement or steel) to satisfy EU27 consumption of goods and services. Three-years moving averages. Source: Authors. Based on Eurostat (2021), IE-LAB and World Bank.

The European Green Deal, EU Recovery and the SDGs

The EU has legislative and policy tools in place, or in preparation, to address most SDG challenges, but it still lacks clarity on how it plans to achieve the SDGs. The European Commission has shown remarkable leadership on the SDGs before and after their adoption. The European Green Deal is the cornerstone for SDG implementation in Europe, yet it contributes directly to only 12 out of 17 SDGs and many social dimensions of the SDGs are not fully reflected in the Green Deal. Due to an absence of politically agreed targets for many SDG indicators, Eurostat in its annual SDG report tracks progress towards quantified targets for only 15 of the 102 indicators. These primarily cover climate change, energy consumption and education. The EU is mainstreaming the SDGs in other policies and instruments, (including recently in its 'better regulation' guidelines), but even seasoned observers can become lost in the plethora of instruments, targets and indicator frameworks that address various SDG challenges. It remains difficult to discern SDG priorities in EU policy processes and roadmaps. Building on the 2020 Staff Working Document and the Council of the EU Conclusions published on 22 June 2021, the EU needs to develop an integrated and comprehensive approach to implementing the SDGs and must communicate clearly on them.

An integrated approach to the SDGs should focus on three broad areas: (i) internal priorities; (ii) diplomacy and development cooperation; and (iii) negative international spillovers. Internally, the concept of SDG Transformations can help the EU frame a narrative that is operational and easy to communicate. By grouping major synergies and any trade-offs, the transformations can focus attention on the greatest implementation opportunities and challenges that the region faces. Building on its Six Transformations framework and others, SDSN proposes six SDG Transformations for the EU that align with the European Green Deal and other EU strategies and policies (see Part 2). In a context in which prioritization of the SDGs and the 2030 Agenda is coming under pressure due to the pandemic and geopolitical tensions, it is crucial that the EU continues to explicitly state its commitment to achieving the SDGs domestically and internationally and connects its policy objectives and mechanisms with them.

We propose four priority actions to accelerate the SDGs in the EU and internationally:

-

Publish a joint political statement from the three pillars of EU governance - the European Council, European Parliament and European Commission - reaffirming their strong commitment to the 2030 Agenda in response to the COVID 19 pandemic and its aftermath, and to renewed momentum towards achieving the SDGs.

-

Prepare a Communication issued by the European Commission clarifying how the EU aims to achieve the SDGs including targets, timelines and roadmaps. This Communication could be updated regularly. It could also show where existing policies need to become more ambitious and where additional policies are required.

-

Set up a new mechanism or renew the mandate of the Multi-Stakeholder Platform for a structured engagement with civil society and scientists on SDG policies and monitoring.

-

Prepare an EU-wide Voluntary National Review ahead of the SDG Summit in September 2023 at the United Nations. The VNR should cover internal priorities, diplomacy, and international actions to restore and protect the Global Commons and address international spillovers.

The EU must lead multilateral Green Deal and SDG Diplomacy, including with China and Africa. EU leadership and diplomacy will be critical to advancing key multilateral processes towards achieving the SDGs: at the UN General Assembly, the High-Level Political Forum on the SDGs, the G7 (under German Presidency in 2022), the G20 (under Indonesian Presidency in 2022), and the Annual Meetings of the IMF and the World Bank. Open dialogue and cooperation with China in areas including vaccine production and distribution, ending COVID-19 globally, infrastructure in Eurasia, and cooperation in Africa will be particularly critical. The sixth EU-African Union Summit, to be held in early 2022, should provide a good opportunity to move towards a new, ambitious partnership with Africa. The EU and member states should also take the lead in mobilizing adequate financial resources from rich countries and rich individuals - who are mostly responsible for the climate and biodiversity crises - to support SDG transformations and climate adaptation in the most vulnerable countries, such as Small Island Developing States. The new Just Transition for South Africa partnership announced at COP26, whereby the UK, United States, France, Germany, and the EU promised $8.5 billion to help South Africa shift from its current dependence on fossil fuels to a clean and renewable electricity system, might pave the way for new forms of cooperation between developed and developing countries.

To ensure international legitimacy, the EU must address negative international spillovers. We underline the negative impacts generated by European countries and rich countries in general through trade and financial flows on the rest of the world. Besides deforestation and environmental impacts embodied into EU's consumption of foreign goods and services, tolerance for poor labour standards in international supply chains can harm the poor, particularly women, in many developing countries. Tax havens and banking secrecy can inhibit other countries' ability to raise the public revenues needed to finance the SDGs. Addressing such spillovers will require coherent trade and external policies through Green Deal Diplomacy, strengthened tax cooperation and transparency, the application of EU standards to exports, and curbing trade in waste. The agreement among 136 economies to move towards a global minimum corporate tax rate goes in the right direction, but the final text remains to be approved for implementation by 2023. The proposal for a carbon- border-adjustment mechanism (CBAM), and other adjustment mechanisms and mirror clauses, may help reduce carbon leakages and other adverse impacts but should be accompanied by increased technical cooperation and financial support to accelerate SDG progress in developing countries. The EU also needs to systematically track such spillovers and assess the impact of European policies on other countries and the Global Commons building notably on the work of the Joint Research Centre, European Environmental Agency and Eurostat on consumption-based accounting.

The Multiannual Financial Framework, NextGenEU and the Recovery and Resilience Facility provide financial firepower to accelerate the transformation of the EU over the period 2021-2027. The Recovery and Resilience Facility has many strengths, as it combines reforms and investments and is, in principle, very much performance-based. Understanding the degree of alignment between member states' National Recovery and Resilience Plans (NRRPs) and the particular SDG challenges they face is an important step to ensure that the Facility meets its objectives to 'guide and build a more sustainable, resilient and fairer Europe for the next generation in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals'. In the context of the Recovery and Resilience Facility, a key challenge will be to ensure that the sum of national recovery plans adds up to coherent and ambitious EU-wide transformations, including transformation of energy and food/land systems.

While few of the NRRPs available make explicit references to the SDGs, an in-depth review of specific measures included in two Plans (Italy and Spain) reveal that all SDGs are addressed, albeit to different degrees. Our in-depth review of NRRPs focuses this year on Italy and Spain: two countries that will receive among the largest funds from the Recovery and Resilience Facility. European Commission guidelines to member states on how to prepare the NRRPs did not explicitly mention the SDGs. Our findings suggest that the SDGs that are most covered by the NRRP, in terms of number of measures and budget allocated, are not always those on which countries face their biggest challenges (as identified in SDSN's SDG Index and Dashboards). In particular, despite relatively poor performances on related goals, measures and funds in the Italian and Spanish NRRPs dedicated to transforming food systems and diets, or to biodiversity goals (covered under SDG 2, SDG 14 and SDG 15), are lower in magnitude than those dedicated to other SDGs.

Transforming food and land systems to achieve the SDGs

The Green Deal, Farm-to-Fork and Biodiversity strategies set high goals for improving the sustainability of EU food and land systems, yet their implementation across EU member states remains challenging. Agriculture is a key area of integration across Europe, with a common European policy in place for almost 60 years. The Commission has provided a set of recommendations to align CAP national plans with these strategies. But in a context in which member states will have higher autonomy to decide on eligible activities under the new CAP, without mandatory targets and clear performance evaluation criteria, there is a high risk that national efforts will not be sufficient to jointly deliver on EU climate and biodiversity objectives.

While Farm-to-Fork is the first holistic strategy of the food system, clear quantitative targets are missing to track progress from the processing and consumption side. Sugar and meat are currently overconsumed in the EU, leading to negative health outcomes (covered in SDG 3, Good health and well-being) and increased health care costs. Moreover, a significant share of the EU ecological footprint generated abroad is related to meat consumption and production in the EU. Multiple studies have shown the global environmental benefits of shifts towards healthier diets, especially for the climate. The EU and individual member states should accelerate the transformation towards sustainable diets including through defining a sustainable and healthy European diet.

Food companies should disclose more information on aspects related to supply chain management and good corporate citizenship. The food industry is key to achieving sustainable food and land systems and should consider greater sustainability as an opportunity for higher economic profitability, resilience, and financial success. The Four Pillar Framework presented in this report covers all corporate activities and can be used by food companies to better align their activities with the SDGs. Moving towards more compulsory requirements - for businesses to monitor and address socio-economic and environmental impacts through their entire supply chains - may help create the right 'level playing field'. Small and medium food companies need support to learn the 'grammar' of sustainability as well as to integrate sustainability principles at the management level. The sharing and valorisation of best practices could help them in this process.

The EU relies extensively on models for policy assessment, but large gaps hinder a comprehensive overview of the potential impacts of Farm to Fork and Biodiversity strategies. Studies that have assessed the impacts of Farm to Fork strategies only look at measures on the production side, assume no changes in the current production systems, and do not include feedback from a better environment on agriculture. Income effects of these strategies on EU producers and consumers in models and the magnitude of spillovers in the rest of the world largely depend on the evolution of prices which are hard to predict. In this context, collaborative modelling initiatives, such as the Food, Agriculture, Biodiversity, Land-Use, and Energy (FABLE) Consortium, can ensure a transparent and inclusive modelling process to support the alignment of national strategies with EU and global sustainability objectives.